The prevalence of physical inactivity in the UK and why this needs to change

Published: 03/09/2021

For the next part in our series, we dig into the prevalence of physical inactivity in the UK, why it should be avoided and how increasing engagement can help improve health outcomes for clients.

As we’ve already explained, physical activity can vary in form and some types are better for us than others. But despite its physical and mental health benefits being widely known and recommended for all ages, the prevalence of physical inactivity in the UK is worryingly high.Most recent global estimates indicate that 27.5% adults1 and up to 81% adolescents2 do not meet the lower limit of the range recommended by the 2020 WHO guidelines for aerobic exercise that we explored in part one.

In the UK, adults are doing worse than the global average, with 35.9% being physically inactive (31.5% for men, 40% for women). Prevalence of physical inactivity has also been increasing over time in high-income countries, increasing by more than 16% between 2001 and 20163.

Physical activity levels are not spread equally

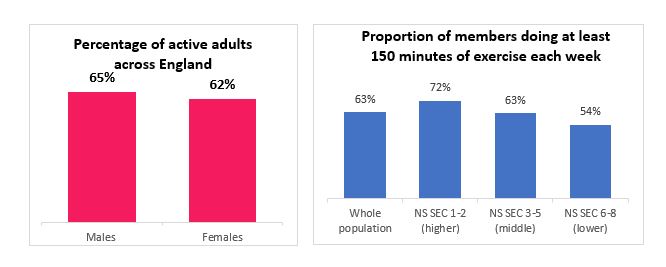

Statistics show that physical levels vary greatly between different social economic groups. Worryingly – but perhaps not unsurprisingly – people in the most deprived parts of the UK are doing far less exercise than those who live in more affluent areas.According to government figures, only around 20% of the least deprived4 individuals in the UK do less than 30 minutes of moderate physical activity a week, while 70% are sufficiently active. In comparison, for the most deprived areas the same figures are 34% and 55%, respectively (a difference of approximately 15 percentage points).

DID YOU KNOW? Evidence shows physical activity can benefit us more the older we get5.

National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (NS-SEC) is the official social economic classification based on occupation in the UK. A rating of eight indicates never being in long-term employment up to one which indicates higher managerial and professional occupations7.

Why does this matter?

There are multiple reasons why insufficient physical activity should be avoided. One of the leading risk factors for death worldwide, reducing sedentary behaviour can dramatically bring down an individual’s overall mortality risk8.Not enough physical activity is estimated to cause 9% of all preventable deaths due to heart disease in the UK9. However, given strong links between physical activity and biometric risk factors, such as high blood pressure, cholesterol, blood glucose and BMI, the actual long-term impact is actually significantly higher. Estimates by Public Health England rank physical activity equal to smoking, causing one in six deaths in the UK and costing up to £7.4bn annually, including £0.9bn to the NHS alone10. Data also suggests that its benefits are even greater for women than they are for men.

More broadly, recently published WHO guidelines11 list physical activity as critical to positive health outcomes for adults. These range from adiposity (weight gain and control) and mental health outcomes, including symptoms of anxiety and depression, to resilience to adverse events in general.

In addition, high-intensity exercise has been proved to benefit us above and beyond light moderate physical activity, through improved overall fitness levels. Cardiorespiratory fitness, the level at which heart, lungs and muscles work together when exercising for an extended period of time, is estimated to have up to twice as much direct impact on risk of premature death13. Measured by VO2 max, this has historically been measured by specific running, treadmill or cycling tests. More recently, however, this has been introduced as a core measure in various wearable activity trackers, helping to raise awareness levels and greatly increasing its accessibility to the general public14.

Why is physical activity beneficial at any level and for all ages?

Analysis done by Vitality shows that while the relative benefits of physical activity are greatest when moving from no to some physical activity – we found overall risk decreases linearly beyond that point. Ultimately, it is always better to do more physical activity (in a way that avoids harm or injury). Adding to this, the magnitude of health improvement increases significantly as we get older.

Coming next: The mental health benefits of physical activity

Insights for the article were taken from our report titled ‘Protective benefits of the Vitality Programme: Physical Activity’ – read the full report.

Where to next?

-

The Vitality Programme

We’re the health insurer that gives your clients’ something back when they get active, meaning they can benefit without having to claim.

-

How Vitality engagement can reduce COVID death risk

Claims data from our parent company Discovery Group shows that engagement in the Vitality Programme could be a factor in saving lives during the pandemic.

-

Insights Hub

Our Insights Hub brings you our range of adviser content - from video series to articles & blogs.

1. Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, et al. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016.

2. Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, et al. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents.

3. The Lancet, 2018

4. Deprivation is defined by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government for 30,000+ small areas in the UK and takes into account income, employment, education, health, crime, barriers to housing and services, and living environment in the given area.

5. Birgitta Langhammer, Astrid Bergland and Elisabeth Rydwik, The Importance of Physical Activity Exercise among Older People, Biomed Red Int, 2018

6. Sport England. Active Lives Adult Survey.

7. Sport England. Active Lives Adult Survey.

8. NCBI, Sedentary Lifestyle: Overview of Updated Evidence of Potential Health Risks, 2020

9. GBD Results Tool.

10. Public Health England. Physical activity: applying All Our Health.

11. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour.

12. Public Health England. Physical activity: applying All Our Health.

13. Darren E.R Warburton, Crystal Whitney Nicol and Shannon S.D Bredin, Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence, CMAJ, 2006

14. Jui-Chuan Cheng, Chao-Yuan Chiu and Te-Jen-Su, Training and Evaluation of Human Cardiorespiratory Endurance Based on a Fuzzy Algorithm, Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2019